Market Insights - June 2023

Market Update | Waiting For Stimulus

Key Points:

After an initial boost tied to its abandonment of zero-Covid, China’s equity market has again underperformed developed markets due to a lacklustre recovery in growth;

China didn’t engage in as much household fiscal stimulus as developed markets, meaning it is not experiencing the inflationary boom other countries did in 2021 and 2022;

Rather, growth has returned to a soggy normal, with the property sector in particular again dragging on outcomes, despite the Government relaxing many of its previous regulatory restrictions on the sector;

Going forward, most expect renewed stimulus from the Government and PBOC, though we think it will be modest, meaning prospects for significant equity market outperformance are limited. However, we think a modest allocation is still warranted due to relative policy settings and growth prospects versus developed markets.

Over the past few years, China’s equity market has been marching to the beat of its own drum. After initially outperforming developed markets during Covid and associated lockdowns, from early 2021 increased regulation of China’s technology companies and Government policy measures to improve housing market sustainability saw a long period of very poor performance. There was a respite from this underperformance in late 2022 as it seemed the worst of the regulatory damage had been done and China abandoned its zero-Covid policy. However, China’s economic recovery following its reopening has been lacklustre, driving relative weakness for much of this year.

In this month’s Market Insight, we review the outlook for China’s economy and what that means for relative equity market performance. Ultimately, like most things in China, this outlook hinges on what the Government chooses to do. Underlying growth remains weak. There has been a little bit of stimulus, but not enough to kickstart a strong recovery. Most think the Government will again have to step up to the crease to deliver a minimum acceptable growth outcome for this year and next.

China’s Great Reopening

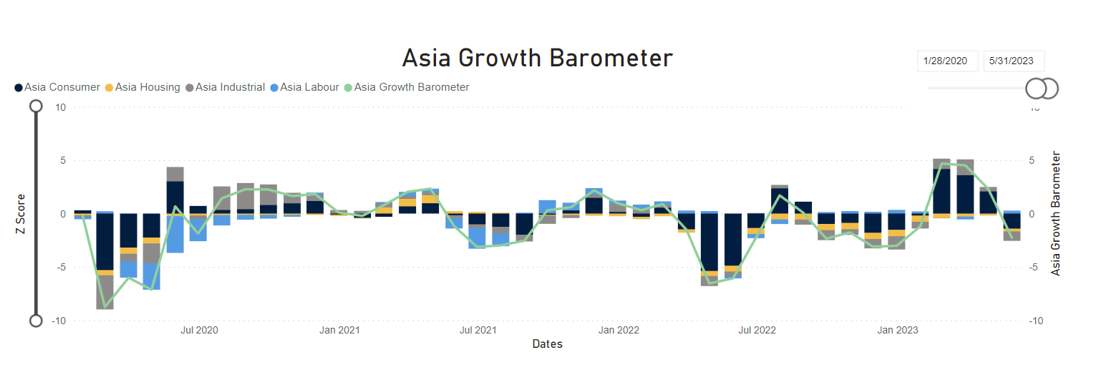

China’s post reopening economic recovery has been a bit of a fizzer. Our Growth Barometer for China (below) shows that after a few months of strong outcomes early this year, growth has again fallen below trend.

As has been the case across most major economies which have exited lockdowns, the immediate growth impulse fades pretty quickly. Mobility in China has returned to normal (see below), which provided a short-term boost, but then little else. During lockdowns, major developed markets engaged in wholesale fiscal stimulus, funnelling large swaths of cash onto the balance sheets of households which were unable to spend it. This author recalls a story from a Melbourne Uber driver who claimed the lockdowns meant he no longer had to live on the brink of insolvency. He and his wife withdrew the maximum allowed from their superannuation, he received job keeper and job seeker and his wife received job seeker. Large cash handouts as an exoneration for lockdowns were common across rich countries. This stimulus has in large part fed strong global growth in 2021 and 2022, leading to the inflationary problems we face today.

Being an authoritarian state with the power to arbitrarily detain problematic citizens, China did not concern itself with placating their aggrieved population in lockdown to the same extent as democratic countries – though it could be argued that protests saw China abandon zero-Covid quicker than planned. As a result, rather than stories of people in Penrith using their superannuation to buy jet skis, China produced stories of families struggling to pay for food and utilities because of lost income. The result of this lack of stimulus is a return to depressed growth rates following their reopening rather than the inflationary boom seen elsewhere.

After a short respite, China’s current weakness again looks to be concentrated in the property sector. Retail spending and fixed asset investment have recovered (though the pace of growth has been slow). However, property sales and new construction projects are again trending lower. Property prices are also again falling.

Running Out of Options

This is likely to be quite concerning for the Government. Housing market activity accounts for around one quarter of the total economy. Initial weakness in housing was sparked by the Government’s Three Red Lines policy, which put caps on three debt ratios and asked property developers to provide more details about their leverage. This sparked a massive correction in the property development sector as few could actually meet the new requirements. Households worried about falling prices and the risk of failed developments stepped away, further undermining activity. Since then, policy restrictions have been relaxed, but sentiment remains weak. A deteriorating external environment also doesn’t help the outlook. Although much of China’s economy is inwardly focused, the export sector is still sizable and with many of China’s trading partners expected to enter recession in the next year, this may also weigh on growth.

In line with this, the market expects renewed stimulus from the Government and People’s Bank of China (PBOC – China’s RBA) to ensure growth targets are met. This month, major interest rates have been cut modestly (see below). The market expects more rate cuts and targeted fiscal stimulus, likely directed at the property sector. The main problem with this is incremental stimulus has so far been unsuccessful at sufficiently stimulating the economy and big bang stimulus is troublesome from a sustainability perspective. China already has a lot of debt, and encouraging households and businesses to load up even further will create even greater problems down the line. Local governments, a large part of the effective delivery mechanism for previous stimulus rounds, are having trouble financing their existing debt repayments given they source much of their revenue from land sales. Much work is being done by central authorities under the hood to restructure the heavy debt burdens of local governments as it is. They can hardly be expected to play the same role again.

Portfolio Positioning

If all of the above sounds depressing, that is because it is. However, there is some important nuance which we think justifies a modest allocation to the region. First, policy settings in China are getting easier, rather than tighter. The government is engaging in fiscal stimulus and deregulating parts of the economy. The PBOC is cutting interest rates. Central banks in developed markets are engaged in significant tightening cycles, which are not yet complete. Secondly, the broad consensus (and our expectation) is for much of the major developed economies to suffer a recession at some point over the next year. While China’s growth is soggy, it is a long way from recessionary territory. Finally, the valuation gap between Chinese equities and developed markets has widened significantly. From a price to book perspective, the Chinese equity market discount is around as large as it has ever been. Why this warrants a modest allocation, rather than a large one, is because of the continued large structural imbalances in China’s economy, any of which could at some point turn soggy growth into a crisis. China’s equity market is cheap for a reason.

If the Government engages in more significant fiscal stimulus and the PBOC slashes interest rates, we would expect a larger relative period of outperformance from China’s equity market. At the moment that doesn’t look forthcoming, but we remain focused on the region and ready to allocate more should that appear more likely.